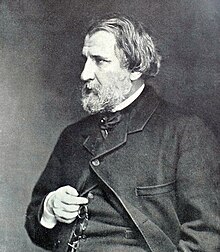

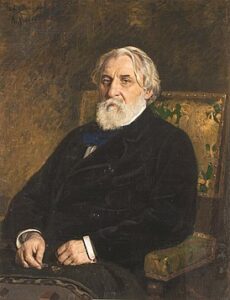

Literary critics contend that the poetics of the novel in the second half of the 19th century was altered by the artistic system established by the classic. In his essay “Fathers and Sons,” Ivan Turgenev demonstrated how he was the first to recognize the rise of the “new man”—the 1960s. The realist author is credited with giving the word “nihilist” its Russian translation. Ivan Sergeevich popularized the term “Turgenev’s girl,” which refers to a fellow countrywoman.

Adolescence and youth

Born into an old noble family in Orel, one of the cornerstones of classical Russian literature. Growing up, Ivan Sergeevich lived near Mtsensk at Spasskoye-Lutovinovo, his mother’s estate. He became the second of Varvara Lutovinova and Sergei Turgenev’s three sons.

The parents’ family life did not succeed. The father, a dashing cavalry guard who had wasted his fortune, wed Varvara, a wealthy girl six years his senior, instead of a beautiful woman. Ivan Turgenev’s father abandoned the family when he reached twelve, leaving his wife to raise their three children. After 4 years, Sergei Nikolaevich passed away. Sergei, the youngest son, succumbed to epilepsy shortly after.

Because of their mother’s autocratic behavior, Nikolai and Ivan had a difficult childhood. Throughout her early years, an educated and clever woman experienced a great deal of sadness. When Varvara Lutovinova’s daughter was a small child, her father passed away. The mother, a tyrannical and irascible woman shown to readers in Turgenev’s story “Death,” was married again. The stepfather battered and humiliated his stepdaughter without hesitation and while drinking. Nor did the mother give her daughter the best of care. The girl ran away from her abusive mother and the beatings she received from her stepfather, and her uncle gave her an inheritance of 5,000 serfs upon her death.

Even though the mother loved the kids, especially Vanya, she did not know affection as a child, so she treated them the same way her parents had treated her. Her sons would always remember their mother’s firm touch. Varvara Petrovna was an educated woman despite her prickly demeanor. She demanded of Ivan and Nikolai that they converse with her family only in French. French novels made up the majority of Spassky’s extensive collection of books.

The family relocated to a home on Neglinka in the city when Ivan Turgenev reached nine years old. Mother was an avid reader who gave her kids a passion for books. Preferring French authors, Lutovinova-Turgeneva was pals with Mikhail Zagoskin and Vasily Zhukovsky and kept up with literary advances. Varvara Petrovna frequently cited Nikolai Karamzin, Alexander Pushkin, and Nikolai Gogol in her correspondence with her son, demonstrating her extensive knowledge of their writings.

Ivan Turgenev received his education from German and French tutors, for whom the landowner paid top dollar. Fyodor Lobanov, a serf valet who later served as the model for the protagonist of the tale “Punin and Baburin,” introduced the future writer to the treasure of Russian literature.

Ivan Turgenev was put to live in Ivan Krause’s boarding home after moving to Moscow. The young master finished his high school education at home and in private boarding houses. At the age of 15, he enrolled in the university in the capital. Ivan Turgenev began his academic career in the Faculty of Literature before moving to St. Petersburg to attend the Faculty of History and Philosophy.

Turgenev translated works by Lord Byron and Shakespeare while still a student, and he aspired to be a poet.

Ivan Turgenev completed his studies in Germany after earning his diploma in 1838. He composed poems and attended a course of university lectures in philology and philosophy in Berlin. Turgenev spent six months in Italy following the Russian Christmas holidays, and then he returned to Berlin.

Ivan Turgenev came in Russia in the spring of 1841, finished his studies, and graduated from St. Petersburg University with a master’s degree in philosophy a year later. He started working for the Ministry of Internal Affairs in 1843, but his passion for books and writing always won out.

The written word

In 1836, Ivan Turgenev made his print debut with a critique of Andrei Muravyov’s book “Journey to Holy Places.” The poems “Calm on the Sea,” “Phantasmagoria on a Moonlit Night,” and “Dream” were written and published by him a year later.

Notoriety arrived in 1843 when Vissarion Belinsky gave his approval for Ivan Sergeevich’s poem “Parasha.” Turgenev and Belinsky soon developed a close relationship to the point where the young author became the godfather of a well-known critic’s son. Ivan Turgenev’s creative biography was impacted by his reconciliation with Belinsky and Nikolai Nekrasov. With the release of the poem “The Landowner” and the stories “Andrei Kolosov,” “Three Portraits,” and “Breter,” the author ultimately bid farewell to the romanticism genre.

In 1850, Ivan Turgenev made his way back to Russia. He composed plays that were well received in the theaters of both major cities when he was living alternately on the family estate and in Moscow and St. Petersburg.

Nikolai Gogol passed dead in 1852. In response to the terrible event, Ivan Turgenev wrote an obituary; however, St. Petersburg refused to publish it at the chairman of the censorship committee’s request, Alexei Musin-Pushkin. Turgenev’s remark was boldly published by the newspaper Vedomosti in Moskovskie. The defiance was not tolerated by the censor. Gogol was referred to by Musin-Pushkin as a “lackey writer” who was unworthy of social recognition. In addition, he perceived in the obituary a suggestion of a transgression of the unwritten rule that prohibited remembering the deaths of Mikhail Lermontov and Alexander Pushkin in public.

Ivan Sergeevich, who was suspected because of his frequent travels outside, contacts with Belinsky and Herzen, and extreme views on serfdom, faced even more fury from the authorities when the censor wrote a report to Emperor Nicholas I.

The following year, in April, the author was placed under house arrest on the estate after being detained for a month. Ivan Turgenev lived in Spassky continuously for a year and a half; he was denied the ability to leave the nation for three years.

Turgenev’s worries that the collection of stories, which had previously appeared in Sovremennik, would not be published separately due to censorship were unfounded. The censorship department official Vladimir Lvov was sacked for permitting the book to be printed. The stories “Bezhin Meadow,” “Biryuk,” “Singers,” and “District Doctor” were among those in the cycle. The novellas were not dangerous taken as a whole, but when read as a whole, they were strongly opposed to serfdom.

Ivan Turgenev wrote for readers of all ages. The author of the prose provided the young readers with richly worded fairy tales and observation stories, such as “Sparrow,” “Dog,” and “Pigeons.”

The famous author wrote “Mumu,” “On the Eve,” “Fathers and Sons,” “The Noble Nest,” and “Smoke” while living alone in a rural area. These works became important parts of Russian culture.

In 1856, Ivan Turgenev traveled overseas for the summer. He finished writing the gloomy tale “A Trip to Polesie” over the winter in Paris. He wrote “Asya” in Germany in 1857; the narrative was translated into several European languages during the author’s lifetime. Turgenev’s daughter Polina Brewer and his illegitimate half-sister Varvara Zhitova are seen by some as the model for Asya, the unmarried daughter of a master and a peasant woman.

Ivan Turgenev kept a careful eye on Russian culture while he was living abroad, keeping in touch with immigrants and writers who were still in the nation. The prose writer was viewed as contentious by colleagues. Turgenev severed ties with Sovremennik, the journal that served as the propaganda tool for revolutionary democracy, due to an ideological dispute with its editors. However, after becoming aware of Sovremennik’s brief ban, he defended it.

Ivan Sergeevich had protracted disagreements with Leo Tolstoy, Fyodor Dostoevsky, and Nikolai Nekrasov during his time in the West. Following the publication of “Fathers and Sons,” he fell out with the so-called progressive literary world.

The first Russian author to be acknowledged as a novelist in Europe was Ivan Turgenev. He made close friends with the Goncourt brothers, Emile Zola, Gustave Flaubert, and realist writers Prosper Mérimée while he was living in France.

When Turgenev came in St. Petersburg in the spring of 1879, the youth welcomed him as a hero. The authorities did not share Ivan Sergeevich’s joy at the famous writer’s arrival, which led him to conclude that the writer should not stay in the city for an extended period of time.

During Ivan Turgenev’s summer visit to Britain that year, the Russian prose writer received an honorary doctorate from Oxford University.

Turgenev visited Russia for the penultimate time in 1880. He saw the inauguration of a monument honoring Alexander Pushkin, whom he regarded as a superb instructor, in Moscow. The Russian language provided comfort and support “in the days of painful thoughts” over the future of the country, according to the classic.

Individual existence

The femme fatale, who eventually won the writer’s heart, was likened by Heinrich Heine to a landscape that is “at the same time monstrous and exotic.” Pauline Viardot was a short, stooped woman with bulging eyes, a wide mouth, and masculine features. She was a Spanish-French vocalist. However, Polina had a fantastic transformation when she sang. Turgenev noticed the vocalist at that very moment and fell in love, a relationship that lasted for the next forty years.

Before she met Viardot, the prose writer’s personal life was a roller coaster. The fifteen-year-old lad was severely injured by his first love, which Ivan Turgenev tragically described in the story of the same name. He fell in love with Katenka, the Princess Shakhovskaya’s neighbor. How disappointing it was for Ivan to discover that his “pure and immaculate” Katya—who mesmerized with her innocent candor and innocent blush—was the mistress of her father, seasoned womanizer Sergei Nikolaevich.

The young man lost interest in the “noble” girls and focused on the simple girls—the women of the serf peasant class. Pelageya, the daughter of Ivan Turgenev, was born to seamstress Avdotya Ivanova, one of the undemanding beauties. However, Avdotya remained in the past when the writer met Viardot while touring Europe.

Ivan Sergeevich got to know Louis, the singer’s spouse, and started going inside their home. Regarding this union, biographers, friends, and contemporaries of Turgenev disagreed. Some describe it as magnificent and platonic, while others discuss the substantial inheritance the Russian landowner left for Polina and Louis. Turgenev’s relationship with his wife was ignored by Viardot’s husband, who let her stay in their home for several months. Ivan Turgenev is thought to be Paul’s biological father. Paul is the son of Polina and Louis.

The author’s mother disapproved of the union and wished for her cherished child to settle down, find a worthy wife, and have lawful grandkids. Pelageya was not Varvara Petrovna’s favorite; to her, she was a serf. Ivan Sergeevich felt sympathy and love for his daughter.

After learning about the girl’s oppressive grandmother’s bullying, Polina Viardot became sympathetic to the girl and welcomed her into her house. After changing into Polynet, Pelageya raised Viardot’s offspring. To be truthful, Pelageya-Polinet Turgeneva felt that the woman had stolen her loved one’s attention and did not share her father’s feelings for Viardot.

Turgenev and Viardot’s relationship cooled down following a three-year break brought on by the writer’s house detention. Twice, Ivan Turgenev tried to put his deadly passion behind him. The 36-year-old writer fell in love with Olga, his cousin’s small daughter, in 1854. But Ivan Sergeevich started to miss Polina when a wedding was imminent. In an attempt to spare the 18-year-old girl from destruction, Turgenev declared his love for Viardot.

Ivan Turgenev made his final attempt to break free from a French woman’s embrace in 1879, the year he turned 61. Since her partner was actually twice her age, actress Maria Savina felt unafraid of the age gap. However, Masha understood she was unnecessary when the couple visited her future husband’s house in Paris in 1882 and she noticed numerous items and mementos that reminded her of her competition.

Death

Following his breakup with Savinova in 1882, Ivan Turgenev became unwell. The discouraging diagnosis of spinal bone cancer was given by the specialists. The writer suffered a long and agonizing death in a faraway nation.

Turgenev had surgery in Paris in 1883. Ivan Turgenev was as joyful as a person racked by anguish can be in the final months of his life, especially with his loving girlfriend by his side. She inherited Turgenev’s estates after her death.

August 22, 1883, was the classic’s death date. On September 27, his body was brought to St. Petersburg. Ivan Turgenev traveled with Claudia Viardot, Polina’s daughter, from France to Russia. The author was laid to rest in St. Petersburg’s Volkov cemetery.