Napoleon Bonaparte was a highly skilled military commander and statesman who also had an extraordinary memory, superb intelligence, and remarkable work ethic. He is the name of a whole age, and most of his contemporaries were shocked by the things he accomplished. His military tactics are taught in textbooks, and the “Napoleonic Law” serves as the foundation for Western democratic principles.

This remarkable individual’s place in French history is unclear. He was referred to be the Antichrist in Spain and Russia, and some historians believe Napoleon to be an exaggerated hero.

Early life and adolescence

Corsican by birth, Emperor Napoleon I Bonaparte was a gifted military commander and statesman. He was born into a lowly noble family on August 15, 1769, in the city of Ajaccio. The future emperor’s parents had eight children. Letizia di Buonaparte, née Ramolino, raised the children while Carlo di Buonaparte, his father, practiced law. Their nationality was Corsican. The surname Bonaparte is a well-known Corsican surname, rendered in Tuscan.

At home, he was taught reading and sacred history. At age six, he was taken to a private school. At age ten, he was sent to Autun College, but he did not stay there for very long. He pursued his studies at Brienne’s military academy after graduating from college. He enrolled in the Paris Military Academy in 1784. After graduating, he was commissioned as a lieutenant and began serving in the artillery in 1785.

Napoleon was a recluse who enjoyed reading and military matters in his early years. While residing in Corsica in 1788, he contributed to the construction of defensive walls, wrote a report on militia organization, etc. He believed that literary works were the most important thing, and he wanted to be well-known in this area.

He is interested in history, geography, the amount of money that European states make, the philosophy of law, and the writings of Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Abbot Raynal. He reads these books with curiosity. Along with writing a history of Corsica, he also keeps a diary and creates the novellas “The Disguised Prophet,” “The Conversation about Love,” and “The Earl of Essex.”

All of the young Napoleon’s writings—aside from one—were kept in manuscript. The author conveys both love and hate for France in these pieces, viewing it as the country that forced Corsica into slavery. The youthful Napoleon’s notes are tinged with politics and brimming with revolutionary energy.

Napoleon Bonaparte enthusiastically welcomed the French Revolution and became a member of the Jacobin Club in 1792. He gained the title of brigadier general in 1793 after defeating the English to take Toulon. This became a pivotal moment in his life story, following which he had an outstanding military career.

Napoleon made a name for himself in 1795 when he put down a royalist uprising. Following this, he was named army commander. His leadership skills were put to the test during the 1796–1797 Italian campaign, which won him recognition across the continent. The Directory dispatched him on a long-range military campaign to Egypt and Syria in 1798–1799.

Despite being defeated at the end, the mission was not deemed a failure. He willingly departs from the army to combat Suvorov’s Russians. General Napoleon Bonaparte makes his way back to Paris in 1799. The crisis facing the Directory government has already reached its peak.

National Policy

He was made consul following the coup and the consulate’s declaration in 1802, and emperor in 1804. Napoleon participated in the publication of a new Civil Code that year, which was based on Roman law.

The emperor’s domestic policy was centered on bolstering his personal authority, which he believed would ensure the retention of the revolution’s victories. He implemented changes in the legal and administrative domains. He implemented several changes in the administrative and legal domains. A few of these inventions continue to serve as the cornerstone for governmental operations. Anarchy was abolished by Napoleon. A law protecting the right to property was passed. France’s citizens were acknowledged as having equal rights and opportunities.

Cities and towns elected mayors, and the French Bank was established. Even the most impoverished segments of society had to admit to themselves that the economy was starting to improve. The army provided an opportunity for the impoverished to make money. Lyceums were established all throughout the nation. The police network grew, a secret department was established, and the media came under heavy restriction all at the same time. Gradually, the monarchical form of administration was restored.

The agreement reached with the Pope, which acknowledged Bonaparte’s authority in return for the declaration of Catholicism as the predominant faith of the majority of people, was a significant development for the French government. About the emperor, society was split into two factions. Although some residents said Napoleon had betrayed the revolution, Napoleon thought he was carrying on its ideals.

International relations

At the start of Napoleon’s rule, France was fighting Austria and England militarily. The menace along the French frontiers was neutralized by a new and successful Italian campaign. Nearly all of the European nations were brought under military rule as a result of the acts. The emperor established kingdoms with members of his family as their monarchs in the areas that did not belong to France. An alliance is formed by Austria, Prussia, and Russia.

Napoleon was first viewed as the nation’s savior. His accomplishments inspired pride among the populace, and the nation saw a rise in unity. But everybody was worn out from the 20-year conflict. The English were compelled to cease dealing with European nations as a result of Napoleon’s declaration of the Continental Blockade, which caused the country’s economy and light industry to collapse. The French port cities were affected by the crisis, which resulted in the cessation of the supply of colonial products to which Europe had already grown accustomed. There wasn’t even enough tea, sugar, or coffee in the French court.

The 1810 economic crisis only made matters worse. The prospect of foreign attack had long since passed, thus the bourgeoisie had no desire to spend money on wars. They saw that the emperor’s foreign policy aimed to uphold the dynasty’s interests and increase his own authority.

When Russian forces routed Napoleon’s army in 1812, the empire started to fall apart. Russia, Austria, Prussia, and Sweden formed an anti-French coalition in 1814, which ultimately led to the fall of the empire. It took down the French that year and made its way into Paris.

Napoleon was compelled to resign, yet his emperorship endured. He was sent to the Mediterranean island of Elba. The banished emperor did not, however, remain there for very long.

Soldiers and civilians in France were dissatisfied with the state of affairs and feared the return of the nobles and Bourbons. After escaping, Napoleon relocated to Paris on March 1, 1815, where the locals welcomed him with jubilant shouts. The military went back into action. This time frame became known as the “Hundred Days” in history. Following the Battle of Waterloo, on June 18, 1815, Napoleon’s army suffered its last defeat.

The English grabbed the overthrown emperor and exiled him once more. This time, he found himself on the island of St. Helena in the Atlantic Ocean, where he spent the next six years of his life. However, not every English person had a bad opinion of Napoleon. George Byron wrote the five poems known as the “Napoleonic Cycle” in 1815 after being moved by the fate of the overthrown emperor. The poet was then criticized for his lack of patriotism. Another English devotee of Napoleon was Princess Charlotte, the future George IV’s daughter, on whose back the emperor once depended. However, she passed away in 1817 while giving birth.

Individual life

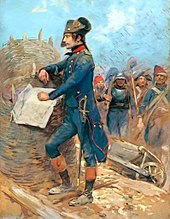

From an early age, Napoleon Bonaparte was well-known for his amorousness. Napoleon’s height of 168 cm, contrary to common assumption, was above normal for those times and could not fail to draw the attention of the other sex. The women surrounding him were drawn to his masculine features and posture, which are evident in copies that are displayed as photos.

Desiree-Eugénie-Clara, 16, was the first girlfriend the young guy proposed to. However, Napoleon’s career in Paris was taking off at the moment, and he was drawn to the allure of the city’s ladies. Napoleon liked to have affairs with women who were older than him in the French capital.

Napoleon’s marriage to Josephine de Beauharnais in 1796 was a significant turning point in his personal life. The love of Napoleon’s life was six years his senior. She was born on the Caribbean island of Martinique into a family who owned plantations. She had two children and got married to Viscount Alexandre de Beauharnais when she was sixteen. She filed for divorce from her husband six years into their marriage, spent some time in Paris, and eventually moved into her father’s home. She returned to France in 1789 following the revolution. She received help from her ex-husband, who at the time was a high ranking government official, in Paris. However, the Viscount was put to death in 1794, and Josephine herself was imprisoned for a while.

After gaining her freedom through a miracle a year later, Josephine met the then-unfamous Napoleon. Some versions claim that she was having an affair with Barras, the French ruler at the time, when they first met, but this did not stop him from attending Bonaparte and Josephine’s wedding. Barras also appointed the groom to the position of commander of the republican Italian army.

The couple, according to researchers, had a lot in common. They both had difficult childhoods, spent time in jail, were born on little islands far from France, and had big dreams. Following the nuptials, Josephine stayed in Paris while Napoleon joined the Italian army. Following the Italian campaign, Napoleon was relocated to Egypt. Although Josephine continued to defy her husband, she relished the social scene in France’s capital.

Enraged by envy, Napoleon developed a preference for some people. Researchers estimate that Napoleon had as many as twenty to fifty lovers. The appearance of illegitimate heirs was the result of a string of affairs that transpired. Charles Leon and Alexander Colonna-Walewski are the two that are known. To this day, the Colonna-Walewski family remains whole. Alexander’s mother was Maria Walewska, a Polish aristocrat’s daughter.

Since Josephine was unable to bear children, Napoleon separated from her in 1810. At first, Napoleon’s goal was to reunite with the Romanov imperial dynasty. He begged Anna Pavlovna’s brother Alexander I for her hand in marriage. However, the Russian monarch was opposed to tying himself to a non-royal ancestor. These differences have a significant impact on the defrosting of ties between France and Russia. Napoleon wed Marie-Louise, the Austrian Emperor’s daughter, who gave birth to his heir in 1811. This marriage did not enjoy the support of the French public.

Paradoxically, it was not Napoleon’s grandson but Josephine’s grandson who went on to become Emperor of France. Denmark, Belgium, Norway, Sweden, and Luxembourg were ruled by her descendants. Napoleon’s son died young and left no children, hence Napoleon had no descendants.

Marie-Louise went to her father’s domains, but Bonaparte anticipated to see his legal wife by his side once they were banished to the island of Elba. Along with her son, Maria Walewska arrived in Bonaparte. Napoleon fantasized of seeing Marie-Louise alone when he returned to France, but the emperor never heard back from Austria despite his repeated letters.

Demise

Bonaparte lived on the island of St. Helena following the loss at Waterloo. He suffered greatly in the final years of his life from an uncurable illness. Napoleon I Bonaparte passed away on May 5, 1821, at the age of 52.

Arsenic poisoning was the cause of death, according to one version and oncology according to another. Supporters of the stomach cancer version point to Bonaparte’s father’s death from stomach cancer as well as the autopsy’s findings and hereditary traits. It is mentioned by several historians that Napoleon was putting on weight prior to his demise. And since cancer patients have weight loss, this evolved into an oblique indicator of arsenic poisoning. Furthermore, following research discovered evidence of elevated arsenic contents in the emperor’s hair.

Napoleon’s testament states that his remains were shipped to France in 1840 and interred anew on the grounds of the cathedral at the Parisian House of Invalids. The sculptures surrounding the former French emperor’s tomb are by Jean-Jacques Pradier.