It is no secret that spiritualizing dead matter has always been a goal for artists. Life-giving statues were sculpted by sculptors from marble, which is a crushed mixture of minerals that was transformed into beautiful paintings by artists. Writers, who wrote before scientists and philosophers, not only described the world of the future in their works, but also enabled common people to view historical events “through new eyes.”

Even now, people’s perspectives of the world are still being completely altered by the writings of Alexandre Dumas, one of the most widely read French authors.

Early life and adolescence

Alexander was born on July 24, 1802, to Thomas Dumas, the “black devil” of Napoleon’s army, and his wife Marie-Louise Labouret. The wealthy family resided in Villers-Cotterêts, a commune in northern France.

The future novelist’s father was an emperor’s close friend and served under Napoleon. Their duet broke apart when the commander—who obeyed the ambitious French ruler’s commands without question—did not agree with his choice to send troops into Egypt.

Not one to take criticism well, Napoleon exacted his customary retribution on his colleague. When the general was taken prisoner in 1801, his influential buddy took no action to release his comrade. General Mack of Austria was traded for Thomas only after he had endured two years of torture and suffering.

The man was sick and tired when he got home. Apart from having stomach cancer, he also had one eye blindness and deafness. Just as swiftly as it had flared up, his star dimmed. After Dumas the elder passed away in 1806, the family had no means of sustenance because they had lost the emperor’s favor.

Because of this, the future well-known author’s early years were marked by devastation and poverty. While his sister fostered in him a love of dance, his mother, who made fruitless attempts to secure a state scholarship to study at the lyceum, began teaching her cherished kid the fundamentals of grammar and reading.

Alexander was able to enroll in Abbot Gregoire’s college, where he learned calligraphy and Latin, thanks to fate’s mercy for the bright young man.

The notary’s office was Dumas’ first workplace, when the young man pretended to be a clerk. The young man had a steady job, but he soon got tired of the same old responsibilities and the never-ending stack of paperwork. The young man packed up his belongings and headed to France’s capital. There, he obtained employment as a scribe in the Duke of Orleans’ (later King Louis Philippe) secretariat thanks to the support of his father’s old ally.

Alexander started his initial artistic endeavors and met local writers at the same time. The drama “Henry III and His Court” was published in 1829, and the author gained notoriety following its premiere. Three years later, “The Tower of Nesle” debuted at the Porte Saint-Martin theater to a completely sold-out house. Seven shows took place on stage in less than 16 months.

The renowned journalist’s life story unfolded in a way that allowed Dumas to participate in society in every manner imaginable. Not only did the author oversee the Pompeii excavations, but he also took part in the Great July Revolution (1830), which resulted in the author being “buried.” A false report that the writer had been shot surfaced in the press following yet another unrest among the populace. In actuality, the author of the “The Three Musketeers” trilogy left Paris and traveled to Switzerland on the recommendation of friends, where he wrote an article titled “Gaul and France” that was eventually published.

Books

The theater was like women under Dumas, full of passion at first, then cold indifference. After mastering the stage, Alexander threw himself into writing.

In 1838, Dumas made his literary debut. Published in a newspaper that demanded a captivating intrigue, quick action, intense passions, and—above all—a chapter structure where the excerpt printed in each issue promised an even more captivating continuation in the following issue—the novel-feuilleton “Chevalier d’Harmental” met these requirements.

Few people are aware that “Chevalier d’Harmental” was written by the young Maquet. However, after being revised by Alexander, the work gained literary brilliance and was published under Dumas’s name alone—not at his request, but at the behest of the customer, who felt that the novel could only succeed if it was published under a well-known name.

Nine cult classics, including The Three Musketeers, The Count of Monte Cristo, The Vicomte de Bragelonne, Queen Margot, Twenty Years Later, The Chevalier de la Maison Rouge, The Countess de Monsoreau, Joseph Balsam, The Two Dianas, and Forty-Five, were published in four years by Dumas and his “colleague.”

The historian had long-held dreams of visiting Russia and had taken numerous trips throughout Europe. His book “The Fencing Teacher” was released in 1840, and the protagonist is the Decembrist Annenkov. Even the docile Empress Alexandra Feodorovna read the controversial masterpiece in secret from her husband, despite the fact that it was censored throughout the Russian Empire.

The writer was granted entry into the empire upon the death of Nicholas I. The author was delighted to discover that, despite being at the birthplace of Alexander Sergeevich Pushkin, the local audience was familiar with French literature and had read some of his works. The well-known author traveled and stopped in places like Kalmykia, Astrakhan, Moscow, St. Petersburg, and even the Caucasus. Travel Notes was a huge hit in the novelist’s native country.

And the publicist was a chef. He goes into great depth about the preparation of specific foods in numerous of his writings.

He sent a manuscript to the press in 1870 that had eight hundred short stories about cuisine. Following the author’s passing in 1873, the “Big Culinary Dictionary” was released. A condensed version known as “The Small Culinary Dictionary” was later released. Dumas was not a glutton nor a gourmet. The man just led a healthy lifestyle, abstaining from coffee, cigarettes, and alcohol.

Individual life

The well-known author’s biggest passion was not, despite common perception, hunting, fencing, or even building. The publicist was most infatuated with the female sex. In the literary salons of the era, stories of the passionate exploits of the erratic playwright were told.

One story in particular stuck out of the many related to the artist’s lovers and spouses.

Dumas had a residence on the Rue de Rivoli at the time with the actress Ida Ferrier, who was well-known for her carefree demeanor. The girl lived in a second-story apartment next to the aspiring writer, who had three rooms on the fifth floor. The two young people were neighbors.

The playwright attended a ball at the Tuileries one evening. The man lost his balance and tumbled into a puddle on the way to the entertainment. After an hour, the irritated publicist came home drenched in mud, proceeded to his wife’s apartment, and stormed into Ida’s bedroom, yelling obscenities. Alexander lost himself in his work, trying to push the unpleasant occurrence from his mind.

After less than thirty minutes, the door to the lavatory opened, and the shocked author was met with a nude Roger de Beauvoir on the doorway, declaring, “I’m frozen, I’m done!” Dumas leaped up and unleashed a torrent of insults on his wife’s lover. Ultimately, the distinguished journalist converted his rage to mercy, saying that his background prevented him from turning away a guest—even one who arrived unexpectedly.

Dumas’s new acquaintance slept in his matrimonial bed that night. Alexander took the hand of the poor man, laid it on his wife’s private area, and declared solemnly when daylight arrived and all three of them were awake.

The dressmaker Laure Labé, who shared the historian’s Place des Italiens home, was his first love. Alexandre was eight years younger than the woman. The seducer had no trouble winning Marie over to his ways; on July 27, 1824, she gave birth to a boy named Alexandre, who is well known to readers of “The Lady of the Camellias” Seven years after the child’s birth, Dumas père gave him recognition.

The two former lovers got together in the city hall on May 26, 1864, to celebrate their son’s marriage to Princess Nadezhda Naryshkina. Dumas fils had considered getting married to his aging parents, but they had not responded to his proposal.

Biographers estimate that the creator had as many as 500 mistresses. Dumas himself said again and time again that he transformed women into gloves only out of charity, since the poor girl would have perished in a week if he had been forced to limit himself to just one.

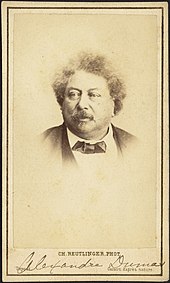

Demise

The renowned author passed away on December 5, 1870. He was laid to rest in Neuville-de-Polle. The son of a famous author reburied his father’s remains among his parents at Villers-Cotterets during the war.

Following the publicist’s passing, biographers proposed the dramatic theory that Alexander Sergeevich Pushkin, the Russian “prophet,” and Frenchman Dumas were one and the same.

Scholars have presented certain data in their works that cast doubt on the veracity of the world literature great’s death.

Although the biographies of both creators have a great deal of “blank spots” and seem identical on the outside, there has never been an official comment on the subject.