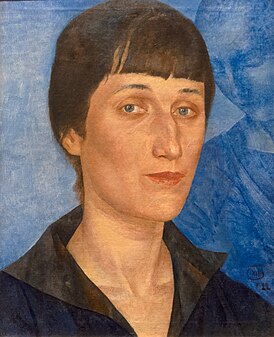

Tragic occurrences plagued the long life of Anna Akhmatova, one of the most brilliant, inventive, and gifted poets of the Silver Age. This self-assured yet delicate woman lived through two revolutions and two world wars. Repression and the passing of her closest friends and family members scorched her soul. The life of Akhmatova is worthy of a book or movie, and writers, directors, and playwrights from a subsequent generation have all attempted to adapt her biography on multiple occasions.

Childhood and youth

The poetess, whose true name is Anna Gorenko, was born in the summer of 1889 into the artistic Odessa aristocratic family of retired navy mechanical engineer Andrei Andreevich Gorenko, a hereditary nobleman, and Inna Erazmovna Stogova. The girl was born at a home in the Bolshoi Fontan neighborhood in the southern section of the city. Her age was revealed to be the third oldest among her six siblings.

The parents went to St. Petersburg as soon as the child turned one year old. There, the head of the family was appointed college assessor and was given special assignment authority inside the State Control. The family made their home in Tsarskoe Selo, where Akhmatova grew up and has all of her childhood memories. The girl was taken for a stroll by the nanny to Tsarskoye Selo Park and other locations where memories of Alexander Pushkin were still present. Social graces were taught to children. Anya studied the French language in her early years by listening to the teacher teach it to older students. She learned to read using the Leo Tolstoy alphabet.

The Mariinsky Women’s Gymnasium was the school where the future poetess acquired her education. Anna claims that around the age of eleven, she started writing poetry. It is notable that she discovered poetry through Gabriel Derzhavin’s majestic odes and Nikolai Nekrasov’s poem “Frost, Red Nose,” which her mother recited, rather than through the works of Mikhail Lermontov and Alexander Pushkin, with whom she fell in love a little later.

Young Gorenko thought St. Petersburg was the primary city in her life and fell in love with it forever. When she had to leave for Evpatoria and subsequently Kyiv with her mother, she truly missed the city’s parks, streets, and Neva. When the girl turned sixteen, her parents were divorced.

Her penultimate grade was done at home in Evpatoria, and her final grade was completed at the Kyiv Fundukleevskaya gymnasium. Gorenko enrolled in the Higher Courses for Women after completing her education, deciding to study law. Though she had a strong interest in Latin and legal history, the girl found jurisprudence to be tedious and uninteresting. Therefore, she pursued her study at N.P. Raev’s historical and literary women’s courses in her beloved St. Petersburg.

Initial inventiveness

“As far as the eye can see,” no one in the Gorenko family pursued poetry study. The poetess and translator Anna Bunina was only related by marriage to Inna Stogova’s mother. The father pleaded not to bring shame to his family name and disapproved of his daughter’s love of poetry. Anna Akhmatova never signed her poems using her true name as a result. She discovered her Tatar great-grandmother, Akhmatova, in the family tree. Akhmatova was said to be derived from Horde Khan Akhmat.

Following her nuptials with Nikolai Gumilyov, Anna Andreevna traveled to Paris for her honeymoon. Akhmatova had never met anyone in Europe before. When the husband returned, he introduced his gifted wife to St. Petersburg’s literary and artistic circles, where she was instantly recognized. Everyone was initially taken aback by her extraordinary, regal beauty and poise. Literary bohemian culture was enthralled by Anna Akhmatova’s “Horde” appearance, which included dark skin and a noticeable hump on her nose.

Writers in St. Petersburg were soon enthralled with the unique beauty’s inventiveness. Writing poems on love during the crisis of symbolism, Anna Andreevna sang about this wonderful feeling her entire life. Young poets experimented with futurism and acmeism, two other fashion fads. Gumileva-Akhmatova became well-known for her Acmeistry.

Her biographies had a breakthrough year in 1912. Not only did the poetess Lev Gumilyov give birth to her sole son in this historic year, but a modest edition of her debut book, “Evening,” was also released. These early works were referred to as “the poor poems of an empty girl” by a woman who, in her final years, had endured all the horrors of the era in which she had to be born and produce. However, Akhmatova gained recognition and her first admirers through her writings.

Alexander Blok served as Anna Andreevna’s mentor, which had an impact on her poetry. The writers corresponded via mail and almost never got together in person—always in front of outsiders. So much for the romance that was supposed to have existed between them. The poetess regarded her instructor as a great representative of the pre-revolutionary generation and held her in the highest regard. To him, she devoted six poems.

In her early years, Akhmatova also got to know Amedeo Modigliani, a gifted but underprivileged artist at the time. He drew and painted multiple portraits of Anna Andreevna. The poetess saved just one drawing till her death; the others were destroyed in the fire in her Tsarskoye Selo home. He later turned up on the covers of her collections, along with some rare photos of the author.

Akhmatova’s second collection, “The Rosary,” was published two years after the first and was immediately hailed as a true triumph. Her work was well received by both critics and admirers, making her the most stylish poetess of her era. Akhmatova was no longer in need of her husband’s defense. Gumilyov’s name sounded less loud than hers.

1917 was a revolutionary year when Anna Andreevna released “The White Flock,” her third work. It was released with an astounding 2,000 copies in circulation.

1918 was a tumultuous year, and the artistic pair parted ways. Additionally, Nikolai Gumilyov was shot in the summer of 1921. The man who introduced Akhmatova to poetry and the father of her son both passed away, and she was in mourning.

IN THE USSR

The poetess experienced hard times starting in the mid-1920s. Akhmatova scribbled poems on tables, many of which were lost during relocation, and fell under the close scrutiny of the NKVD, who stopped publishing her. 1924 saw the publication of the final collection. Poetry that were labeled as “provocative,” “decadent,” or “anti-communist” cost Anna Andreevna a great deal.

Coworkers showered Akhmatova with affection and appreciation. Boris Pasternak and Marina Tsvetaeva were two of them, and they were far more excited about her work than she was about theirs. It should be noted that both writers passed away before the tragically brief life of Anna Andreevna.

The new phase of his creation was intimately linked to his heartbreaking concerns for his loved ones, especially his kid Levushka. The first red flag went up for the widow in the late fall of 1935 when her son Nikolai Punin, her second husband, was detained simultaneously. A few days later, they were freed, but the poetess’s life was no longer peaceful. Akhmatova could sense the circle of repression closing in on her from that point on.

My son was taken into custody three years later. His sentence included five years of hard labor in camps. The weary mother delivered packages to Lev. Anna Andreevna and Nikolai Punin’s marriage terminated in that dreadful year of 1938.

The poetess released the book “From Six Books” in 1940, right before the war, in an effort to ease her son’s situation and get him out of the camps. Old poems that had been suppressed and recently published poems that were deemed “correct” by the governing ideology were gathered here. The well-known autobiographical poetry “Requiem,” which Akhmatova had been working on since 1934, was finished the same year.

When the Great Patriotic War broke out in the city on the Neva, Anna Andreevna was moved to Tashkent. She returned to a liberated and destroyed Leningrad immediately following the war, and she quickly relocated to Moscow.

However, the clouds that had just begun to break as the boy was let free from the camps quickly became thicker once again. Her work was destroyed at the next Writers’ Union meeting in 1946, and Lev Gumilyov was detained once more in 1949. He received a 10-year sentence this time. The poor woman was shattered. She sent letters of apology and petitions to the Politburo, but she never heard back.

The relationship between mother and son remained difficult for many years after Lev’s release from yet another prison term; he felt that Akhmatova prioritized poetry over him.

It was only towards the end of her life that the extremely unhappy and well-known woman’s situation began to improve. Her poems started to appear in publications once more in 1951 after she was accepted back into the Writers’ Union. After publishing the collection “The Running of Time,” Anna Andreevna was awarded a major Italian prize in the middle of the 1960s. The renowned poetess also received a doctorate from Oxford University.

By then, Akhmatova had developed into a mentor for promising writers. She was the one who therefore recognized Joseph Brodsky’s special natural gift. When they first met in 1961, the latter was just 21 years old.

The renowned author and poet at the end of his days at last acquired a house of his own. She received a humble wooden dacha in Komarovo from the Leningrad Literary Fund. It was a tiny cottage with a veranda, a corridor, and one room. A door-shaped table, an old icon that had once belonged to the first husband, a Modigliani drawing on the wall, and a hard bed with bricks in place of legs comprised the entire furnishings.

Individual existence

Anna Akhmatova had incredible influence over males. When the poetess was younger, she was incredibly adaptable. It’s said that she could effortlessly stoop backwards and touch the ground with her head. This amazing dance of nature so astounded even the Mariinsky ballerinas. She also has incredible color-changing eyes. There were those who stated Akhmatova’s eyes were sky blue, those who said they were green, and still others who believed they were gray.

Wedlock with Nikolai Gumilyov

The girl met Nikolai Gumilyov, the renowned poet, when she was a little girl and a student at the Mariinsky Gymnasium.

At first sight, Gumilev fell in love with Anna Gorenko. However, the girl was completely enamored with Vladimir Golenishchev-Kutuzov, a student who ignored her. The young student struggled and even made an attempt to hang herself with a nail. Fortunately, he managed to escape the clay wall.

The girl wrote to Gumilyov in Evpatoria and Kyiv; the correspondence captivated her and diverted her attention from the poignant scene. In 1910, the couple made the decision to tie the knot in the spring. They were married in the St. Nicholas Church, located in the village of Nikolskaya Slobodka, close to Kiev. The church is still standing today. Nikolai Stepanovich was already well-known in literary circles and a skilled poet at the time.

The poetess composed “The Gray-Eyed King” after the wedding. Although the dedication is unknown, literary experts believed that the piece conveyed the breakdown of girlish dreams associated with marriage and that the author did not love her spouse.

The first spouse loved Anna Andreevna for the entirety of his brief life, but he also had an illegitimate kid that everyone knew about in addition to his common son Lev with Akhmatova. Furthermore, Nikolai Gumilyov could not comprehend why his beloved wife, who he believed to be a mere poetess, inspired such joy and even exaltation in the eyes of the youth. He found Anna Akhmatova’s love poetry to be overly verbose and haughty. They eventually split up.

In Akhmatova’s life, other men

It appears that the daughter of Inna Erasmovna inherited her mother’s shortcomings. She was not happy when married to any of the three recognized husbands. Their and her own infidelity caused chaos and disharmony in Anna Akhmatova’s personal life.

Following her split from Gumilyov, Anna Andreevna attracted a large following. Although the beautiful Nikolai Nedobrovo took precedence over Count Valentin Zubov, who was overwhelmed by her presence and offered her armfuls of pricey roses. But Boris Anrepa took his place shortly after.

She divorced her second husband a year after her first one passed away. And she tied the knot for the third time six months later. The artist Nikolai Punin was a critic. However, Anna Akhmatova’s familial life also proved to be unsuccessful for him.

She was also not thrilled with Anatoly Lunacharsky Punin, the Deputy People’s Commissar of Education, who had taken in Akhmatova after her divorce and left her homeless. The new spouse contributed money for food into a communal pot while sharing an apartment with Punin’s ex-wife and his daughter. Son Lev, adopted from his grandmother, felt abandoned and unloved when he was left alone in a chilly hallway at night.

After meeting with pathologist Vladimir Garshin, Anna Akhmatova’s destiny might have been different, but shortly before the wedding, he is said to have dreamed of his late mother, who pleaded with him not to bring a witch into the house. The nuptials were called off.

Death

Even though Anna Akhmatova was now 76 years old and had been very ill for a long time, her death on March 5, 1966, seemed to come as a shock to everyone. The poetess passed away at a Domodedovo sanitarium close to Moscow; heart failure was listed as the reason of death. She requested to have the New Testament brought to her on the eve of her death so that she might compare its contents with those found in the Qumran manuscripts.

The authorities did not want dissident trouble, so they moved quickly to get Akhmatova’s body from Moscow to Leningrad. The Komarovskoye cemetery is where the poetess was laid to rest. The mother and son were never able to get back together before they passed away; they were silent for a number of years.

Lev Gumilyov built a stone wall with a window at his mother’s grave; the wall was meant to represent the wall in the “Crosses,” where she delivered packages for him. As desired by Anna Andreevna, a wooden cross was initially placed on the tomb; however, in 1969, a stone cross was added.

Memory

Through her writing, Akhmatova touched many people’s hearts, and Anna Andreevna’s memory lived on beyond books after her passing. In several Russian cities, monuments and plaques were placed in her honor; streets, courts, parks, and libraries were all given her names.

Avtovskaya Street in St. Petersburg is where the Akhmatova Museum first opened. She spent thirty years living in the Fountain House, where another one was opened. Subsequently, the poetess’ home cities of Moscow, Tashkent, Kyiv, Odessa, and numerous others saw the installation of memorial signs and bas-reliefs.