The vicissitudes of the fate of Peter I (1672–1725), the last Russian Tsar and the first All-Russian Emperor, have fascinated journalists, politicians, and researchers for the past three centuries. Peter I was the first All-Russian Emperor. In order to restructure Russian society, the great reformer divided the history of the country into two distinct eras: the “Petrine” era and the “pre-Petrine” age. Some of the improvements that he brought about are still happening today. In some way or another, all of Peter I’s activities in domestic and international affairs could be summed up in one thing: the Emperor’s goal was to strengthen the military and technical capabilities of the nation, to create a “window to Europe,” and to take the most successful accomplishments of European culture.

The early years of Peter I’s life

Peter the First was born on May 30th, 1672, which is also known as June 9th. Natalya Kirillovna Naryshkina was the second wife of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich, and Peter Mikhailovich was the eldest son between the two of them. In addition to being reared by nannies, the heir to the throne was taught to read and write by Nikita Zotov, a clerk who did not have a very high level of education. I did not receive a European education that was organized in a methodical manner, I did not learn reading and writing until a later age, and I wrote with errors. The young prince, on the other hand, was always marked by his insatiable quest for education and spent his entire life picking up new skills and information. He had a passion for learning crafts and was fluent in a number of different languages.

I did not receive a European education that was organized in a methodical manner, I did not learn reading and writing until a later age, and I wrote with errors. The young prince, on the other hand, was always marked by his insatiable quest for education and spent his entire life picking up new skills and information. He had a passion for learning crafts and was fluent in a number of different languages.

Already in early childhood, the prince also demonstrated an interest for military science. For Peter’s games, a “funny” regiment was formed from peers of the future emperor. Peter and his pals staged demonstration battles, assaulted fortifications, and even brought artillery to their amusements. Gradually, the “game of toy soldiers” transformed into true military-practical training, and adults began to engage in the entertaining games. From the Tsarevich’s childhood games, the legendary Peter the Great’s army of the new system later grew, and the amusing ones themselves became its elite guards units – the Preobrazhensky and Semenovsky regiments.

Reign of Peter I

The route of the future emperor to power was not easy. The machinations of opposing boyar families, brutal Streltsy riots and the fight with his elder sister Princess Sophia overshadowed the first years of the rule of Peter I. The emperor carried out the drastic reforms that followed against the backdrop of the hard Northern War. The victory did not make the emperor rest on his laurels for long – the tireless autocrat, the “eternal worker” on the throne, labored till the end of his days for the majesty and glory of the empire.

Accession of Peter I.

Early years Tsar Fyodor Alekseevich, Peter’s elder brother, did not reign for long. He died in 1682, leaving the question of succession to the crown open. A furious conflict broke out between two boyar families – the Naryshkins and the Miloslavskys. Peter’s brother Ivan hailed from the Miloslavskys, and by seniority he was intended to take the throne. However, the Boyar Duma decided to crown the robust and intelligent Tsarevich Peter, and not Ivan, a feeble man and little capable of administering the realm.

In an attempt to keep control, the Miloslavskys fabricated a tale that Tsarevich Ivan had been assassinated by the Naryshkins. A bloody Streltsy rebellion broke out. On May 15 (25), 1682, an agitated mass of armed people burst into the Kremlin. Although Ivan came before the archers alive and undamaged, the insurrection continued until numerous boyars were slaughtered. As a result, the throne was shared by both claimants for the throne. Ivan V was appointed the “first” tsar, and Peter I was appointed the “second”. Tsarevna Sofya Alekseevna became their regent, and in fact the ruler of the state.

The reign of Princess Sophia lasted until 1689. Peter matured, got married, which allowed him to officially get rid of his sister’s guardianship, and began to exhibit his own strength. There was also a military force behind him – those hilarious regiments loyal to the emperor, which had long ceased to be “toys”. Tsar Ivan did not take any part in state matters. After his death on January 29 (February 8), 1696, authority officially transferred into the hands of Peter.

The penultimate attempt by Sophia and her entourage to return to controlling the state happened in 1698, when, during Tsar Peter’s vacation abroad, a new Streltsy riot broke out in Moscow. The revolt was brutally repressed. The mass murders of Streltsy went recorded in history as one of the deadliest pages of Peter the Great’s reign.

Beginning of Russian expansion, 1690–1699

In the 90s of the 17th century, Peter I’s foreign strategy was aimed to the south. Under Princess Sophia, Russia embarked into a war with the Ottoman Empire, and the responsibility of the young monarch was not to lose this conflict. Peter I the Great complied with this mission brilliantly: the Treaty of Constantinople in 1700 reinforced Russia’s position in the south, and the ruler moved his focus to the northern frontiers of the realm.

In the spring of 1697, the legendary Grand Embassy journeyed to the countries of Western Europe. It had to solve many problems: enlist the support of European rulers in the fight against Turkey and Sweden, study the state of military and engineering, the political system of the European powers, invite foreigners to Russian service, purchase weapons and other goods that were not produced at home. The ambassador visited Austria, Holland and England. A visit to Venice and even to the Pope was planned, but the Streltsy rebellion stopped the tsar’s journey. Peter I personally took part in the embassy anonymously, under the identity of the sergeant of the Preobrazhensky Regiment, Peter Mikhailov, but his extraordinary appearance and personal involvement in the discussions gave the royal away.

During his journey, Peter I intensively examined Western technology. In the Dutch town of Saardam, and subsequently in the English Deptford, the king studied the science of shipbuilding and worked in shipyards. He toured hospitals, industries, museums, colleges, and was interested in a range of crafts – from engraving skills to methods of embalming corpses. It is claimed that it was the Grand Embassy that formed the trigger for the Europeanization of Russia under Peter I.

Creation of the Russian Empire, 1700–1724

The process of modernization and Europeanization of Russia took occurred against the backdrop of arduous and extended battles. In pursuit of money, troops and labor, Peter had to deploy all the resources of the state, resorting to harsh persecution. But toward the conclusion of Peter’s reign, Russia joined the European stage as a great military and economic force, and Peter on October 22 (November 2), 1721, accepted the title of Emperor of All Russia and Father of the Fatherland.

Foreign policy

A long battle with the Ottoman Empire in the south, a hard Northern War with Sweden, and expansion to the east – these were the primary directions of the foreign policy of the great reforming sovereign. But this foreign policy was not carried out by arms alone. The triumphs of Peter’s diplomacy are related with the formation of strong connections with foreign governments, which were fostered by journeys to Europe and Peter’s personal contact with the kings of the main nations.

Military campaigns

The biography of Peter the Great is in many respects a history of the battles that Russia undertook during his reign. The valiant king never hid in the rear. In the toughest fights, in the midst of things, beneath bullets, he risked his life and inspired soldiers and leaders with his heroics.

Azov campaigns

As soon as Peter obtained genuine, rather than nominal leadership in the Russian state, the battle with the Ottoman Empire needed all his strength.

The major target of the Russian army was the Azov citadel, the seizure of which allowed Russia access to the sea. The first Azov campaign in 1695 ended in defeat. The young tsar knew that it would not be feasible to assault the citadel without the backing of warships, and work started to boil at the Voronezh shipyards. Money for the fleet was gathered “by the whole world”: the king ordered the creation of “kumpanships”, in which peasant proprietors united, and each such kumpanship had to build and equip a ship. A year later, Russia started its second battle not only with land forces, but also with the Marine Regiment – the precursor of the contemporary marine corps. Azov was captured.

Great Northern War

By the beginning of the 18th century, Peter’s foreign policy moved to Europe – the Tsar resolved to restore the holdings in the Baltic. Russia could not fight alone and on two fronts, thus the Northern War began only when a ceasefire was signed with the Ottoman Empire and the “Northern Alliance” was created – an anti-Swedish alliance of Russia, Denmark, Saxony and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The commencement of the Northern War turned out to be tough for our country. After the defeat of the Russian army at Narva on November 19 (30), 1700, it became evident how disastrous Russia’s gap was in the military, industrial and economic areas.

Peter I extensively reformed the administration of the army, modified the supply system, put industry at the service of the army, established shipyards and a fleet. The outcome was not long in coming: barely two or three years later, the Russians reached the Baltic Sea shore at the entrance of the Neva, taking the fortifications of Noteburg and Nyenschanz and commencing the building of St. Petersburg. By 1704, Peter seized Narva and Dorpat, and on June 27 (July 8), 1709, he utterly destroyed the Swedish monarch Charles XII at the Battle of Poltava. Among the biggest successes of the nascent Russian navy are the battles of Gangut in 1714 and Grengam in 1720. Peace with Sweden was signed on August 30 (September 10), 1721 at Nystadt. Russia captured extensive Baltic areas (Ingria, Karelia, Estonia and Livonia) and acquired access to the sea.

Russo-Turkish War 1710–1713

In 1710, the Sultan launched war on Russia, and Peter had to fight on two fronts. The Emperor personally led his forces towards the Danube, where he intended to obtain the assistance of Christians subjugated to Turkey. This campaign of 1711 ended disastrously for Russia. The army was encircled near the Prut River. The troops suffered greatly from dehydration and starvation, the king himself and his entourage were threatened with incarceration – they had to implore the Turks for peace.

The Prut Peace Treaty with the Ottoman Empire, and later the Peace of Adrianople in 1713, permitted Peter to continue the struggle with Sweden, but took away all his prior southern victories. Azov was restored to Turkey, Taganrog was devastated, Russia lost the Azov navy and access to the sea. However, these terms were substantially gentler than those to which Peter, who was anxiously dashing around in the Prut trap, had first consented.

Advancing East

Despite the continuous battles in the European portion of Russia, Peter the Great continued to develop the eastern areas – Siberia, Central Asia, and the Far East. Companion of the sovereign I.D. Buchholz embarked on an expedition to Siberia in 1714 and established the Omsk stronghold south of the Irtysh. In 1716–1717 Prince A. Bekovich-Cherkassky was despatched to the Khiva Khanate with a big troop. He was meant to persuade the Khiva Khan to surrender, examine if it was feasible to mine gold in the Amu Darya, and possibly pave the route to India. Bekovich’s mission ended in failure: all his troops perished or were captured, and the leader himself was slain.

Under Peter, aggressive development of the Far East, particularly Kamchatka, continued. Since 1708, the peninsula formed part of the Yakut region of the Siberian province. It was at the initiative of the emperor, after his death, that Vitus Bering’s journeys to America across the Pacific Ocean were planned.

Caspian (Persian) campaign

In 1722–1723 Russia, under the authority of Emperor Peter, embarked into a new war – with Persia. The purpose of the Persian (Caspian) campaign was to capture the lands of southern Transcaucasia and Dagestan. In 1722, Derbent succumbed to the Russian army and fleet, and in 1723, the western side of the Caspian Sea, including the citadel of Baku, submitted. The involvement of the Ottoman Empire prevented future conquests, and a few years after the death of Peter, the Caspian regions were restored to Persia.

Reforms of Peter I

The tremendous developments during Peter the Great’s period influenced all aspects of Russian reality. Among the primary ones are military, administrative, economical and ecclesiastical reforms.

Military reforms

The disintegration of the Streltsy army and the development of an army of the “new system”, that is, a regular force structured according to the European model, constituted the first stage of large-scale military reforms. Over a few of decades, Peter “from scratch”, and sometimes with his own hands (remember his studies at the shipyards of Saardam and Deptford) developed a fleet with all its infrastructure – shipyards, admiralties, logging companies.

Gradually, most of the foreigners in military service were replaced by well-trained Russian officers. The process of recruiting the army also altered. In 1705, Peter I imposed conscription, which extended to all classes. For the aristocrats it was a personal obligation, for the tax-paying classes it was a collective one. The recruit left his home forever: his term of service under Peter was everlasting.

Public Administration Reforms

Peter the Great did not have a clear plan for public administration improvements. The king aspired to minimize the power of the Boyar Duma and to build an effective administrative vertical. In 1711, Peter founded the Governing Senate – the highest body of collegial governance of the kingdom “instead of His Tsar’s Majesty himself” when the restless Russian Tsar was gone. Gradually, the Senate acquired legislative, administrative and judicial duties.

By the beginning of the 18th century, the intricate system of orders had totally outlived its usefulness, and Peter gradually got rid of it. The new management bodies – the collegiums – had to explicitly apportion among themselves the tasks of the prior departments, make the administrative system visible and speed up its operation. The number of collegiums fluctuated; the primary ones were regarded to be the Military, Admiralty and Foreign Affairs. To supervise the actions of the increased bureaucratic structure under Peter, the prosecutor’s office and the institute of fiscals were founded.

Church reform

Peter, with his ambition to submit all areas of existence to the requirements of the state, could not come to terms with the independence of the church. He dissolved the patriarchate and conciliarity of the church, and changed its ruling body, in actuality, into one of the collegiums – the Holy ruling Synod (1721). Thus, the church was thoroughly interwoven into the power structure with the despotic tsar at its apex.

Currency reform

The quest for finances to wage war continuously consumed Peter. In the initial years of his reign, the treasury was almost empty, and the king came up with fresh and new means to fill it: direct and indirect taxes were instituted, the mandatory use of stamp paper was mandated, and the weight of coinage was lowered. The fundamental monetary unit under Peter was not the old money, but the penny.

A fundamental restructure of the country’s financial system was prompted by the shift to a new type of taxation – the capitation tax (and not the household tax, as before). This needed periodical population censuses, as the money necessary to support the army, navy and government was now split not by the number of houses (peasant households), but by the number of male souls. Despite the shortages and inaccuracy of the censuses, this reform at least increased the size of the treasury.

Transformations in industry and trade

The growth of industry and the development of the country’s raw materials were one of the major objectives of the king-transformer. According to Peter’s regulations, geological research of mineral riches and the development of industries were pursued across Russia. A robust metallurgical base was built in the Urals. Those desiring to engage in the development of mineral resources were allowed numerous rights; along with state-owned industries, private ones also arose.

The conflict with Sweden led Peter to forgo the acquisition of metal overseas. At the outset of the conflict, church bells were melted down into cannons, and by the conclusion of the reign of Peter I, Russia not only ceased to depend on the import of metal, but also began to export it to Europe. The Tula and Sestroretsk armaments manufacturers produced rifles, cannons and bladed weapons to the entire army and spared the treasury from spending on acquisitions overseas. Light industries also emerged, particularly leather and textiles. Peter promoted domestic merchants and manufacturers, creating varying levels of tariffs for Russian and foreign merchants, but did not ban the import of those commodities that were not accessible in Russia.

Class politics

Pyotr Alekseevich’s ambition to govern state life also altered the structure of society: under him, the rights and obligations of various classes gained shape, the slavery of the peasantry deepened, and a new type of peasant reliance developed – attachment to manufactories.

At the same time, the borders of classes under Peter became movable. The establishment of the Table of Ranks made possible a “social lift”: from now on, high standing in society might be achieved not by birth, but by effort and talent. The table of ranks separated all levels of military, civil and court service into 14 classes, and upon attaining the 8th class, any employee or officer acquired personal nobility. The rights of the ancient clan boyars were therefore essentially obliterated.

Education reform

The Tsar-Reformer was, surely, also the Tsar-Educator. He sent young people to study abroad, brought European academics and technological specialists to Russia, and created educational institutes for educating military and naval officers, engineers, and physicians. From 1701 until 1721, a school of mathematical and navigational sciences, artillery, medical, engineering schools and a naval academy began functioning in Russia.

Peter also did not forget about mass education, with his decrees supporting the creation of “digital schools” to educate youngsters literacy and numeracy. For the nobles and clergy, education became required under Peter. The Tsar fostered book publishing, carried out a typographical type reform, and began printing the first newspaper in Russia. Not limited himself to colleges that taught practitioners, Peter set out to construct a scientific center that would be in no way inferior to the famed European academies. Thus was created the notion of constructing an Academy of Sciences, which would contain a university and a gymnasium. The inauguration of the Academy took place a year after the death of Peter I.

Calendar and time reform

In the 17th century, the commencement of the New Year in Russia was celebrated on September 1, and chronology was measured from the Creation of the world. On December 20, 1699, the Tsar ordered to celebrate the New Year on January 1, and the chronology shall be carried out from the Nativity of Christ, as in Europe. True, Peter lived according to the Julian calendar, therefore Russia celebrated the advent of 1700 10 days later than the great majority of European governments. We also owe our holiday customs to Peter: in a special edict, the Tsar tightly regulated the whole schedule of public festivities, required that fireworks be ignited, masquerades be staged, and even detailed how to adorn a Christmas tree.

Peter also organized the time count. If earlier the day and night hours were measured by the sun, varying based on the time of year, now the reference points were connected to noon and midnight, according to the European model.

Personality of Peter I

The vivid and exceptional personality of the king is the topic of constant dispute among historians and public leaders. A superb commander, the sharpest administrator and trendsetter – or a brutal autocrat who destroyed the original identity of Russian society? It is hard to provide an unequivocal appraisal to the biography of Emperor Peter I.

Peter I had an amazing look and an equally remarkable character. He was tall (203 cm) and quite slim, with lovely facial features, which, nevertheless, were sometimes disfigured by nervous tics – the emperor suffered from them from his boyhood. Contemporaries highlighted Peter’s bright intelligence, his ingenuity, justice, simplicity and honesty in his contacts with both the greatest nobles and regular troops. The nature of Peter I did not allow half measures, neither in wrath, nor in affection, nor in labor, nor in repose. The monarch also experienced bursts of wrath, during which the king was exceedingly harsh. He was not averse to carousing all night long, and he delighted to chastise people close to him with the famed royal club.

Marriage and children

The personal life of Peter the Great can scarcely be considered joyful. His first marriage, finalized at the age of 17 with Evdokia Lopukhina at the request of his mother, was not successful. From this marriage, Peter had a son, Alexei, heir to the throne, who, however, did not at all share the reforming ideals of his dad. After a series of confrontations with his father, the Tsarevich escaped abroad, was returned from there, convicted of treason, and died under mysterious circumstances in captivity after the death sentence was pronounced.

The second bride of the autocrat was the maid Marta Skavronskaya, seized in the Baltics, and subsequently Empress Catherine I. Peter adored and protected her till the end of his life, and only she could control the monarch’s terrible temper. Ekaterina Alekseevna became the mother of 11 children, but practically all of Peter the Great’s children perished in infancy, which cost the Tsar a lot of pain.

Death and will

In the later years of his life, the king was severely sick. His health was harmed by the difficulties of battle, hard work, and chaotic adolescence. The emperor perished in horrible pain on January 28 (February 8), 1725. The reason of Peter I’s death was inflammation and gangrene of the bladder.

Peter’s legislation on succession to the throne left the choice of a successor totally to the whim of the king. Ironically, the emperor himself, dying, did not have time to choose the name of the next sovereign. By resolution of the Senate, Catherine I gained the throne.

Results of the board

The reforms and conquests of Peter the Great made Russia one of the major military and industrial powers in Europe. Peter built a new cultural environment in Russia, modified the economy, political structure, style of life, food, fashion and even leisure. The emblem of Peter’s reforms became the new sumptuous capital of the empire – St. Petersburg.

However, not everyone loved the home policies of Peter I: for the brutality of his changes and a dramatic departure with all national customs (including the prohibition on wearing Russian attire and growing beards), the emperor was frequently called the “Tsar Antichrist.”

Not all of Peter’s alterations were maintained by his successors, but the emperor’s initiatives defined the vector for the growth of Russia until the very end of the 18th century.

To dissuade them from rebelling against the prince in the future, he levied a tribute twice as high as previously. Since then, the Drevlyans have held a deep animosity against him.

To dissuade them from rebelling against the prince in the future, he levied a tribute twice as high as previously. Since then, the Drevlyans have held a deep animosity against him.

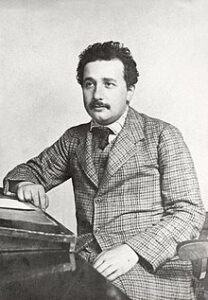

Albert Einstein started attending the Luitpold Gymnasium in 1888, having completed his elementary education at a nearby Catholic school. His strongest subjects were Latin, physics, and math. In addition, he enjoyed reading books on philosophy and science, particularly Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason and Euclid’s Elements. He went on to say that he rejected the drill-and-cram approach to typical German schooling during these years and instead became independent in his thinking.

Albert Einstein started attending the Luitpold Gymnasium in 1888, having completed his elementary education at a nearby Catholic school. His strongest subjects were Latin, physics, and math. In addition, he enjoyed reading books on philosophy and science, particularly Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason and Euclid’s Elements. He went on to say that he rejected the drill-and-cram approach to typical German schooling during these years and instead became independent in his thinking.

He relinquished his German citizenship, his membership in the Prussian and Bavarian Academies of Sciences, and his connection with the scientists who stayed in Germany after moving to the United States. His signature on a 1939 letter to US President Franklin D. Roosevelt regarding the threat of nuclear weapons development in Germany had an impact on the US government’s decision to launch the Manhattan Project.

He relinquished his German citizenship, his membership in the Prussian and Bavarian Academies of Sciences, and his connection with the scientists who stayed in Germany after moving to the United States. His signature on a 1939 letter to US President Franklin D. Roosevelt regarding the threat of nuclear weapons development in Germany had an impact on the US government’s decision to launch the Manhattan Project.

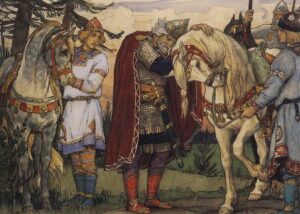

A war was launched against Constantinople in 907; the city is referred to as Constantinople in various texts. A trade deal was signed in 911 as a consequence. It states that Russian traders were unable to pay taxes for goods sold in Constantinople and were allowed to stay for free for six months at the monastery of St. Mammoth. Byzantine money was used to pay for their allowances and ship repairs. A mutual peace pact was also in place between the two nations.

A war was launched against Constantinople in 907; the city is referred to as Constantinople in various texts. A trade deal was signed in 911 as a consequence. It states that Russian traders were unable to pay taxes for goods sold in Constantinople and were allowed to stay for free for six months at the monastery of St. Mammoth. Byzantine money was used to pay for their allowances and ship repairs. A mutual peace pact was also in place between the two nations. several agreements. Oleg dispatched envoys to verify the state of peace; upon their return, they carried presents. According to one account, rather than the Tale of Bygone Years, he was nicknamed Prophetic for his wisdom and caution throughout the Byzantine battle.

several agreements. Oleg dispatched envoys to verify the state of peace; upon their return, they carried presents. According to one account, rather than the Tale of Bygone Years, he was nicknamed Prophetic for his wisdom and caution throughout the Byzantine battle.