Gorbachev, Mikhail Sergeevich, was the first and only President of the Soviet Union (1990-1991), and he was also the final General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (1985-1991). The individual who served as the Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union from 1988 to 1989 was Mikhail Gorbachev. Subsequently, he became the first Chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union from 1989 to 1990. A period of time known as “perestroika” occurred under the reign of Mikhail Sergeevich. This era of time resulted in a shift in the way of life in Russia as well as the political situation across the world. In 1990, Mikhail Sergeevich Gorbachev was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. At the same time, many people in the post-Soviet zone blamed the previous leader for the demise of the Soviet Union.

Mikhail Gorbachev passed away on the 30th of August, 2022.

the early years of Mikhail Gorbachev and his educational background

On March 2, 1930, Mikhail Sergeevich Gorbachev was born in the Russian village of Privolnoye, which is located in the Medvedensky district of the North Caucasus area (which has been known as the Stavropol region only since 1943).

Mikhail Gorbachev’s father, Sergei Andreevich Gorbachev, was born in Russia in 1909 and passed away in 1976. During the Great Patriotic War, Sergei Andreevich served as a participant and was subsequently honored with two Orders of the Red Star as well as the medal “For Courage.”

Maria Panteleevna Gorbacheva, a Ukraine-born woman, is Mikhail Gorbachev’s mother. She was born Gopkalo in 1911 and passed away in 1993.

Both grandfathers of Mikhail Gorbachev were repressed in the 1930s. His paternal grandpa, Andrei Moiseevich Gorbachev (1890−1962), was an individual peasant. In 1934, he was deported to the Irkutsk area for failure to comply with the planting plan. However, two years later he returned home and joined the collective farm.

Maternal grandfather – Panteley Efimovich Gopkalo (1984−1953) originating from the Chernigov province. Having moved to the Stavropol district, he became the head of a communal farm. However, in 1937 he was suspected of Trotskyism and jailed. According to Wikipedia, Mikhail Gorbachev’s grandpa was rescued by a shift in the “party line” – the famous February 1938 plenum dedicated to the “fight against excesses.”

After the resignation and fall of the USSR, Mikhail Gorbachev remarked that his grandfather’s stories served as one of the elements that pushed him to reject the Soviet dictatorship.

When the war began, my father went to the front, and the family found themselves under occupation. In 1943, these territories were freed. Misha Gorbachev worked at MTS from the age of 13 while continuing to study in school. In 1949, Mikhail was given the Order of the Red Banner of Labor for his hard work, and at the age of 19 he became a candidate member of the CPSU.

In 1950, Mikhail Gorbachev obtained secondary schooling, graduating from school with a silver medal. As someone who got a government grant, the young guy joined Moscow State University without tests. M.V. Lomonosov . Thus, a young guy from Stavropol was able to get higher education at a top Moscow institution.

Career of Mikhail Gorbachev

In 1952, Mikhail Sergeevich Gorbachev became a member of the CPSU.

Gorbachev graduated with honors from the Faculty of Law in 1955 and was posted to Stavropol to the regional prosecutor’s office. However, he worked there for barely 10 days. As is known from the biography of Mikhail Gorbachev, he was invited to the vacant Komsomol position, becoming deputy director of the agitation and propaganda department of the Stavropol Regional Committee of the Komsomol.

This was a fantastic start to his party career. Since 1956, Gorbachev has been the first secretary of the Stavropol city committee of the Komsomol, and in 1961-1962, Mikhail Sergeevich was the first secretary of the regional committee of the Komsomol.

Mikhail Sergeevich Gorbachev swiftly ascended the career ladder. In October 1961, Gorbachev was a delegate to the XXII Congress of the CPSU. In 1962, Mikhail Gorbachev was chosen party organizer of the regional committee of the Stavropol territorial production collective and state agricultural administration. Then he began working as the head of the department of party bodies of the Stavropol Regional Committee of the CPSU. The young party worker Gorbachev was deemed one of the most promising.

On September 26, 1966, Mikhail Sergeevich was elected first secretary of the Stavropol City Committee of the CPSU. At the same time, Gorbachev continued to study – in 1967, he graduated in absentia from the Faculty of Economics of the Stavropol Agricultural Institute with a degree in agronomist-economist.

The biography of Mikhail Gorbachev on the website of his foundation speaks about this era as follows. “The Stavropol Territory is one of the most beautiful and famous resort places in Russia. Top party leaders of the USSR routinely came here to rest. It is here that M.S. Gorbachev met A.N. Kosygin and Yu.V. Andropov . Gorbachev built a deep and trustworthy friendship with Andropov. Later, Andropov would brand Gorbachev a “Stavropol nugget.”

The biography of Mikhail Sergeevich Gorbachev on Wikipedia claims that Gorbachev was twice offered for the role of head of the KGB section. But she was rejected by Vladimir Semichastny . However, Yuri Andropov still viewed Mikhail Sergeevich as a prospective contender for the role of deputy chief of the KGB of the USSR.

In 1970, Mikhail Gorbachev became the first secretary of the Stavropol Regional Committee of the CPSU. His predecessor in this role, Leonid Efremov , remarked that Gorbachev’s career acquired pace at the demand of Moscow.

1974−1989 Mikhail Gorbachev was a deputy of the Council of the Union of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR for the 9th–11th convocations. During this era, Mikhail Sergeevich was a member of the nature conservation commission and was the head of the Youth Affairs Commission of the Union Council of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR.

According to Gorbachev (as mentioned in his biography on Wikipedia), he was patronized by Yuri Andropov. Mikhail Sergeevich also had powerful allies – Mikhail Suslov and Andrei Gromyko sympathized with him .

It is known that Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev himself authorized the nomination of the young party functionary for the post of Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee.

On November 27, 1978, during the plenum of the CPSU Central Committee, Mikhail Sergeevich Gorbachev was elected Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee, following which he came with his family in Moscow. Two years later, he became a member of the party’s highest governing body – the Politburo of the CPSU Central Committee.

General Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee

After a succession of consecutive general secretaries, concluding with the death of Konstantin Chernenko , it was Gromyko who proposed Mikhail Gorbachev to the role of general secretary. This happened on March 11, 1985.

Next, Mikhail Sergeevich Gorbachev served as Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR, combining it with the top post in the party hierarchy (since 1988).

Mikhail Gorbachev began reforms called “Perestroika.” Gorbachev’s biography on his foundation’s website says that during these years “a program was being developed to transfer the economy to a socially oriented market basis” and “the dismantling of the totalitarian regime in the USSR took place.” Accordingly, Gorbachev’s critics believe that Mikhail Sergeevich was engaged in dismantling the state and nothing else.

At the end of 1986, Soviet scientist and dissident, Nobel Prize laureate A.D. returned from political exile. Sakharov. Under Gorbachev’s authority, criminal prosecution for dissent stops.

During this era, Mikhail Gorbachev switched companies to self-financing, self-sufficiency, and self-financing. This was the introduction of the first components of a market economy in the USSR, the broad adoption of cooperatives – the forerunners of private firms, and the easing of limitations on foreign exchange transactions.

In 1985, the “Gorbachev Prohibition Law” was announced. Alcohol prices were increased, sales were curtailed, vineyards were chopped down, and sugar needed for moonshine was given out on ration cards. This led to a rise in the use of moonshine and surrogates, and caused a blow to the budget. But during this era, mortality reduced, life expectancy improved, and the number of crimes linked to drunkenness decreased. “I think that the anti-alcohol campaign was a mistake in the way it was carried out. This overlaps with the closing of stores, notably in Moscow. Huge lineups. The rise of moonshine. Sugar disappeared from shelves. Sobering up society cannot be done in a haste. This takes years. I think that even now we need to battle alcoholism,” Gorbachev himself commented on his “prohibition law” 30 years later.

In January 1987, at a meeting of the Politburo of the CPSU Central Committee, which debated the duty of top party cadres, the first serious public disagreement between Gorbachev and Yeltsin occurred . From this time on, Mikhail Sergeevich was often chastised by Boris Yeltsin, and a rivalry between the two leaders began.

In 1990, authority shifted from the CPSU to the Congress of People’s Deputies of the USSR, a parliament elected in free democratic elections. On March 15, 1990, Mikhail Sergeevich Gorbachev was elected president of the USSR. And until December 1991, Gorbachev was also the Chairman of the USSR Defense Council, the Supreme Commander-in-Chief of the USSR Armed Forces.

Foreign policy under Mikhail Gorbachev

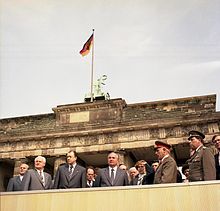

“In international relations, Gorbachev pursued an active policy of détente based on the principles of “new thinking” that he formulated and became one of the key figures in world politics of the twentieth century. During 1985−1991, there was a fundamental transformation in ties between the West and the USSR – a move from military and ideological conflict to discussion and the creation of partnership relations. Gorbachev’s initiatives had a crucial influence in ending the Cold War, the nuclear weapons race, and the unification of Germany,” says the biography of Mikhail Sergeevich. Gorbachev’s critics believe that the withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan, the fall of the Berlin Wall, the liquidation of large groups of Soviet troops abroad (GSVG, TsGV, YuGV, SVG, GSVM) and the collapse of the Warsaw Pact meant the defeat of the USSR in the Cold War, for which the Secretary General was to blame. President Mikhail Sergeevich Gorbachev.

On December 8, 1987, Mikhail Sergeevich Gorbachev and US President Ronald Reagan signed an open-ended Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty in Washington, which went into force on June 1, 1988

In 1989-1990, Mikhail Gorbachev played a crucial role in the unification of Germany, while Margaret Thatcher and Francois Mitterrand sought to slow down the pace of the integration process, not wanting a new “domination” of Germany in Europe.

The Moscow Treaty on the Final Settlement with Germany, which was agreed upon by Mikhail Sergeevich and signed on behalf of the USSR on September 12, 1990 by Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze , stated that foreign troops and nuclear weapons or their carriers will not be stationed or deployed on the territory of the former GDR. In a stunning interview with Oliver Stone, Vladimir Putin characterized the acts of Gorbachev, who in 1990 did not formally codify the “non-expansion of NATO,” a “mistake.” Gorbachev himself, reacting to Putin, stated that he did not comprehend this claim.

In an interview with RG, Gorbachev noted that “the question of “NATO expansion” was not discussed or arose at all in those years,” the question was raised of “promoting NATO military structures and the deployment of additional armed forces of the alliance on the territory of the then GDR.”

“The decision of the United States and its allies to expand NATO to the east was finally formed in 1993. From the very beginning I labeled this a major error. Of obviously, this was a breach of the spirit of the promises and guarantees that were provided to us in 1990. As for Germany, they were legally established, and they are being observed,” said Mikhail Sergeevich.

Nowadays, Mikhail Gorbachev highlighted such successes of his rule as freedom, openness, freedom to go abroad, freedom of religion. “Finally, disarmament. People just sighed. Everyone, generally speaking, all across the world, especially in the developed world, in Europe and America, was digging bunkers against a nuclear war, which may break out at any moment. This was all done. It’s over,” Gorbachev believes .

On October 15, 1990, Mikhail Gorbachev was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. Speaking in Oslo with the Nobel lecture, Mikhail Sergeevich emphasized the desire of the peoples of the USSR “to be an organic part of modern civilization, to live in accordance with universal human values, according to the norms of international law,” according to Gorbachev’s biography on Wikipedia.

The 1991 putsch and Mikhail Gorbachev

On August 19, 1991, the foundation of the State Committee for the State of Emergency in the USSR (GKChP) was announced. The report claimed that the country’s President Mikhail Gorbachev was unwell and Vice President Gennady Yanaev , Chairman of the State Emergency Committee , took up his duties .

Boris Yeltsin assembled his comrades-in-arms to the White House to “repel the junta.” On August 20, it became evident that the State Emergency Committee was losing against Yeltsin, who organized a crowd at the White House to repel the “putschists” and support Gorbachev, who was unjustly taken from office. On the night of the 21st, in a tunnel on the Garden Ring, three people perished under the rails while trying to halt armored vehicles, and in the afternoon Gorbachev was rescued from Foros. This was followed by arrests by the Russian prosecutor’s office of members of the State Emergency Committee and those leaders who actively backed it.

According to Mikhail Sergeevich himself and those who were with him, he was isolated at Foros (according to the testimony of certain former members of the State Emergency Committee, their allies and lawyers, there was no isolation).

On August 24, 1991, Mikhail Gorbachev announced his resignation as General Secretary of the Central Committee. “I immediately saw and understood – this is a different Gorbachev. He was morally damaged and demoralized. Therefore, for the next two or three months he became a captive, really a prisoner of Yeltsin,” Ruslan Khasbulatov recalled Gorbachev after the State Emergency Committee in an interview with SP.

In November 1991, Mikhail Sergeevich Gorbachev quit the CPSU, but preserved his party card as a remembrance.

On November 4, 1991, the head of the USSR Prosecutor General’s Office for supervision over the implementation of state security laws, Viktor Ilyukhin , opened a criminal case against Gorbachev under Article 64 of the Criminal Code of the RSFSR (treason) in connection with his signing of resolutions of the USSR State Council of September 6, 1991 recognizing the independence of Lithuania , Latvia and Estonia. USSR Prosecutor General Nikolai Trubin closed the case due to the fact that the decision to recognize the independence of the Baltic republics was taken not by the president directly, but by the State Council.

Collapse of the USSR

On December 8, 1991, President of the RSFSR Boris Yeltsin, President of Ukraine Leonid Kravchuk and Chairman of the Supreme Council of the Belarusian SSR Stanislav Shushkevich signed the Belovezhskaya Agreement on the termination of the existence of the USSR and the foundation of the CIS.

Russian Vice President Alexander Rutskoi convinced Gorbachev to arrest Yeltsin, Kravchuk and Shushkevich. But Gorbachev responded amorphously: “Don’t panic… The arrangement has no legal foundation… They will fly in, we will convene at Novo-Ogarevo. By the New Year there will be a Union Treaty!”

25 years later, Mikhail Sergeevich revealed why he did not arrest them; according to Gorbachev, the atmosphere “smelled like civil war.”

On December 21, by resolution of the Council of Heads of State of the CIS, convened in Almaty, the leaving President of the USSR earned lifelong benefits: a special pension, medical care for the whole family, personal protection, a state dacha, and he was allocated a personal automobile. The settlement of these concerns was assigned to the Government of the RSFSR. Also, the participants at the conference in Almaty actually robbed Gorbachev of the authority of the Supreme Commander-in-Chief, handing the command of the Armed Forces of the USSR “until they are reformed” to Air Marshal Evgeny Shaposhnikov .

Accusations of Mikhail Gorbachev for the demise of the USSR

Gorbachev’s administration is still widely debated in society today. Many believe Mikhail Sergeevich to be the perpetrator of the fall of the USSR, as a result of which Russia almost lost its sovereignty. But the former Soviet leader finds such criticism unwarranted.

Currently, Mikhail Gorbachev likes to maintain that he is not to blame for the fall of the USSR and tried everything to rescue the nation. “I always only wanted to reform the USSR, but I never aimed at the collapse of the country. I regret that a big power with huge powers and resources has perished. To tell the truth, if I were still in office, it would continue to exist,” Gorbachev was quoted in the news in 2016.

On the question of the fall of the USSR and blame for it, Mikhail Gorbachev clashed with the first President of Ukraine Leonid Kravchuk. Kravchuk said at his press conference that it was Ukraine that destroyed the Soviet Union in 1991, which he called “the last empire, the most terrible.” Gorbachev, in an interview with the National News Service, said that the main culprit for the collapse of the USSR was former Russian President Boris Yeltsin. And former member of the CPSU Central Committee Kravchuk, according to him, began to make such comments owing to age-related changes.

Kravchuk, in a statement to NSN, recalled the age of Gorbachev himself. According to him, Gorbachev is to responsible for everything, as, having announced perestroika, he did not manage it, but it carried on by itself, while Mikhail Sergeevich lived and stated common truths on his own.

Later, Mikhail Gorbachev again asserted that it was Russia that caused the fall of the Soviet Union, blaming then-President Boris Yeltsin of blame for what transpired. “The union could have been saved. The republics required a rebuilt Union. The fall of the Soviet Union was precipitated by the participants in the Belovezhskaya Accords, led by personal aspirations and a craving for power. This is, first of all, the then leadership of Russia,” the media quoted Gorbachev’s statement at the end of 2016.

According to director Nikita Mikhalkov , in order to lead Russia out of the crisis, it is important to recognize at the governmental level the crimes of Gorbachev and Yeltsin, who were culpable of the breakup of the USSR. “Nothing can be built without clearing the site. And removing the site involves admitting the crimes of Gorbachev and Yeltsin at the state level. They committed an actual crime. Willingly or unknowingly, led by aspirations or not by ambitions, that’s not what we’re talking about today. Their successes contributed to the demise of our country! And this is the worst geopolitical tragedy that has transpired this century!”

In 2017, Mikhail Gorbachev remarked that he thought it conceivable for a new Union State to arise inside the borders of the old Soviet Union. “The Soviet Union is no, but the Union is yes. I feel that there may be a new Union. Within the same borders and with the same composition, voluntarily,” the ex-president was quoted as saying in the news.

Personal life of Mikhail Gorbachev

In the personal life of Mikhail Gorbachev there only one woman – his wife Raisa Maksimovna. While studying at Moscow State University, Mikhail Gorbachev met Raisa and on September 25, 1953, married a student at the Faculty of Philosophy, Raisa Maksimovna Titarenko (1932−1999). The Gorbachevs had their wedding in the dining area of the student dormitories on Stromynka.

After several years of looking for work in her profession, Raisa Gorbacheva began teaching at the Faculty of Economics at the Stavropol Agricultural Institute. Raisa Maksimovna provided lectures to students and graduate students on philosophy, aesthetics, and questions of religion. Then Mikhail Gorbachev’s wife defended her candidate’s dissertation on the theme “Formation of new features of the life of the collective farm peasantry (based on sociological research in the Stavropol Territory).”

n January 6, 1957, the Gorbachevs gave birth to a daughter, Irina, who presently resides in Moscow. Irina has two grown children, Gorbachev’s granddaughters Ksenia and Anastasia are already married, and she has a great-granddaughter Alexandra. Irina Gorbacheva is a doctor by training, educated at the Second Medical Institute named after. N.I. Pirogova. She was engaged in scientific activity and did research in the field of medical demography and sociology. In 1985 she defended her PhD thesis on the subject of life expectancy for males in the USSR. Irina’s second degree is management; in 1995 she graduated from the International Business School at the Academy of National Economy under the Government of the Russian Federation. Irina Gorbacheva-Virganskaya is vice-president of the Gorbachev Foundation.

The Gorbachevs enjoyed a long and happy life, but in 1999, Mikhail Sergeevich was widowed – his wife Raisa Gorbacheva died of leukemia, which was a severe loss for the former USSR president.

In 2009, the album “Songs for Raisa” was published (along with Andrei Makarevich )

After quitting large politics, Mikhail Gorbachev starred in advertising. Mikhail Sergeevich marketed the Pizza Hut restaurant business, Louis Vuitton accessories, computers, and Austrian trains.

In 1993, Gorbachev played himself in Wim Wenders’ feature film So Far, So Close! In 2007, Mikhail Sergeevich participated in the documentary film by Leonardo DiCaprio “The Eleventh Hour”.

In 2004, he got a Grammy Award for scoring Sergei Prokofiev’s musical fairy tale “Peter and the Wolf” jointly with Sophia Loren and Bill Clinton , Wikipedia writes in the section “Gorbachev’s acting activities.”

Mikhail Gorbachev at now, health situation.

The former president of the USSR is the founder of the Gorbachev Foundation. Since 1993, Mikhail Sergeevich has been a co-founder of CJSC Novaya Dezhednevnaya Gazeta (Novaya Gazeta) and a member of the editorial board.

At the end of September 2015, Vladimir Zhirinovsky launched a lawsuit against former USSR President Mikhail Gorbachev. The chairman of the LDPR was angry that the former head of the Soviet Union dubbed him a provocateur in his book “After the Kremlin.” Zhirinovsky wanted to publish a response, and also to compensate him for moral damages in the sum of 1 million rubles. The Timiryazevsky court of the Russian capital partially satisfied the claim to safeguard the honor, dignity and business reputation of the leader of the LDPR and his party, opting to collect 6,300 rubles as legal fees from the first and at the same time final president of the USSR.

In the fall of 2016, the media propagated the word that the Vilnius District Court planned to call the former President of the Soviet Union Mikhail Gorbachev as a witness in the case of the January 1991 events, when fifteen people died during disturbances in the capital of Lithuania. The press staff of the Gorbachev Foundation responded that they had not received any documentation concerning Gorbachev being summoned for interrogation and added that the ex-USSR president had regularly spoken out in his books on the matter of the events in Vilnius in 1991.

In 2015, it became known that Mikhail Gorbachev’s health was also failing. He suffers from a severe form of diabetes, his condition cannot be considered stable, as quite often the politician has crises, as a consequence of which he needs to be quickly hospitalized in a clinic to stabilize his general health. In 2015, they even disseminated “news” regarding Gorbachev’s death, although Mikhail Sergeevich turned out to be alive.

The notice regarding the death of former USSR President Mikhail Gorbachev was published on the German microblog RIA Novosti on Twitter and on the official Twitter channel of the agency’s worldwide multimedia press center. As it turned out, RIA Novosti channels were hacked, and Gorbachev himself responded on his “death” as follows: “They are hoping in vain. Alive and healthy. I wonder who doesn’t like it.”

In April 2015, the automobile in which the first president of the USSR was was engaged in an accident in the north-west of Moscow, although Mikhail Gorbachev himself was not hurt.

Mikhail Gorbachev currently actively continues to conduct creative activities, releasing new scientific works and publishing memoirs. In 2014, Mikhail Gorbachev’s book “Life after the Kremlin” was published, and earlier he released a book of memoirs about the love of his life, “Alone with Myself.” On February 29, 2016, the Gorbachev Foundation hosted a presentation of the new book “Gorbachev in Life,” according to Mikhail Gorbachev’s Wikipedia page. Mikhail Sergeevich often appears in the news and speaks out about modern politics. Gorbachev, for example, claims that he knows how to improve relations between Russia and the United States.

He also asks Vladimir Putin to apply his expertise. Mikhail Gorbachev deems Putin a “worthy president” and a “strong personality,” but admits that he opposed a number of his policies.

In 2016, Russian President Vladimir Putin thanked the first and last president of the USSR, Mikhail Gorbachev, on his 85th birthday.

In a congratulatory letter published on the Kremlin’s official website, Putin observed that everyone “knows Mikhail Gorbachev as a bright, extraordinary person, a prominent statesman and public figure.”

Currently, Gorbachev positively considers the actions of the current Russian President Vladimir Putin, backing his position on Crimea and Ukraine.

In 2016, Free Press reported that former Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev was placed on a list of people banned from visiting Ukraine for five years. As noted in the news, the reason for this decision was Gorbachev’s support for the return of Crimea from Russia, which he expressed in an interview with the British publication The Sunday Times. Press Secretary of the Russian head of state Dmitry Peskov , commenting on the news, “expressed regret at the next expansion of the list of persona non grata, especially at the expense of such veterans of our and world politics as Mikhail Gorbachev.”

Former President Gorbachev now lives in a Moscow apartment and at a dacha near Moscow. In February 2017, news appeared that the family of the former president of the Soviet Union, after ten years of use, put the villa in Germany up for sale. Mikhail Gorbachev lived mostly alone in a house near Lake Tegernsee, and in recent years he came to Bavaria extremely rarely. As the mayor of Oberach, Christian Kok , said , local residents used to often meet Gorbachev on the streets and in restaurants; the ex-president was a landmark of the region.

The total area of the 3-storey 17-room villa Hubertus-Schloessl (“Hubertus-Schloessl”) is 2.6 thousand square meters, its living area is 600 square meters. The Gorbachev family purchased this property in 2006. The real estate agent expects to receive seven million euros for the land plot along with the house.

In 2017, Mikhail Gorbachev won the winner of the “Lion Award” for 2017, which was founded by the humanitarian organization Human Projects and is given “For services to achieving peace and reconciliation.”

Death of Mikhail Gorbachev

On August 30, 2022, the first president of the USSR, Mikhail Gorbachev, died at the age of 92. This was recorded at the Central Clinical Hospital.

On August 30, 2022, the first president of the USSR, Mikhail Gorbachev, died at the age of 92. This was recorded at the Central Clinical Hospital.

“This evening, after a serious and long illness, Mikhail Sergeevich Gorbachev died,” the Central Clinical Hospital stated.

Joseph Stalin died on March 5, 1953 in the government dacha at the age of 73 (74) years due to a cerebral hemorrhage that developed on March 1 against the background of the development of hypertension and atherosclerosis. The formal news of death followed the next day. The country went into mourning. The funeral, arranged on an unprecedented magnitude for the country, took place on March 9, 1953 in Red Square in Moscow.

Joseph Stalin died on March 5, 1953 in the government dacha at the age of 73 (74) years due to a cerebral hemorrhage that developed on March 1 against the background of the development of hypertension and atherosclerosis. The formal news of death followed the next day. The country went into mourning. The funeral, arranged on an unprecedented magnitude for the country, took place on March 9, 1953 in Red Square in Moscow.

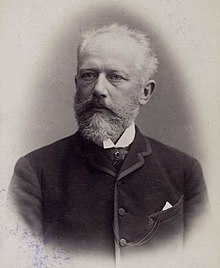

e Snow Maiden ” to the music of Tchaikovsky took place at the Maly Theater in Moscow. In 1875, Tchaikovsky’s opera “ The Oprichnik ” was presented at the Bolshoi.

e Snow Maiden ” to the music of Tchaikovsky took place at the Maly Theater in Moscow. In 1875, Tchaikovsky’s opera “ The Oprichnik ” was presented at the Bolshoi. In the fall of 1893, Pyotr Ilyich was offered unboiled cold water in a restaurant on Nevsky. This became the source of a dreadful sickness – cholera, from which Tchaikovsky died unexpectedly a few days later, on October 25, 1893, at the apartment of his brother Modest.

In the fall of 1893, Pyotr Ilyich was offered unboiled cold water in a restaurant on Nevsky. This became the source of a dreadful sickness – cholera, from which Tchaikovsky died unexpectedly a few days later, on October 25, 1893, at the apartment of his brother Modest.

However, even after the act of church canonization, many who are opposed to this act say that the declaration of Nicholas II as a saint was of a political character. On the other hand, among certain segments of the Orthodox community, the concept that praising the Tsar as a passion-bearer is not sufficient is gaining weight. On May 6, 1868, Nicholas II, the first son of Emperor Alexander III and Empress Maria Feodorovna, was born at Tsarskoe Selo. He was the first of his family’s children. As befits the heir to the royal throne, he was provided with an outstanding education. During Nikolai’s early youth, the Englishman Karl Osipovich Heath, who resided in Russia, served as his teacher. Subsequently, General Grigory Grigorievich Danilovich was designated as Nikolai’s formal teacher as the heir to the position.

However, even after the act of church canonization, many who are opposed to this act say that the declaration of Nicholas II as a saint was of a political character. On the other hand, among certain segments of the Orthodox community, the concept that praising the Tsar as a passion-bearer is not sufficient is gaining weight. On May 6, 1868, Nicholas II, the first son of Emperor Alexander III and Empress Maria Feodorovna, was born at Tsarskoe Selo. He was the first of his family’s children. As befits the heir to the royal throne, he was provided with an outstanding education. During Nikolai’s early youth, the Englishman Karl Osipovich Heath, who resided in Russia, served as his teacher. Subsequently, General Grigory Grigorievich Danilovich was designated as Nikolai’s formal teacher as the heir to the position.

In 1867, he joined the pacifist group “League of Peace and Freedom” and made a speech at its 1st congress, aiming to transform it into an anarchist society. In 1868, he broke with the League, joined the Geneva section of the First International, and at the same time organized the “Alliance of Socialist Democracy,” not much different from the anarchist “International Brotherhood.” Bakunin makes enormous efforts to ensure that the Alliance is accepted into the First International, and he succeeds on the condition that the Alliance as a union is dissolved. But he maintains a secret organization within the International and wages a fierce struggle with Mars and Engels on the most important political and theoretical issues, putting forward as the main provisions the equality of classes, the abolition of inheritance as the starting point of social progress, and abstinence from participation in the political movement.

In 1867, he joined the pacifist group “League of Peace and Freedom” and made a speech at its 1st congress, aiming to transform it into an anarchist society. In 1868, he broke with the League, joined the Geneva section of the First International, and at the same time organized the “Alliance of Socialist Democracy,” not much different from the anarchist “International Brotherhood.” Bakunin makes enormous efforts to ensure that the Alliance is accepted into the First International, and he succeeds on the condition that the Alliance as a union is dissolved. But he maintains a secret organization within the International and wages a fierce struggle with Mars and Engels on the most important political and theoretical issues, putting forward as the main provisions the equality of classes, the abolition of inheritance as the starting point of social progress, and abstinence from participation in the political movement.